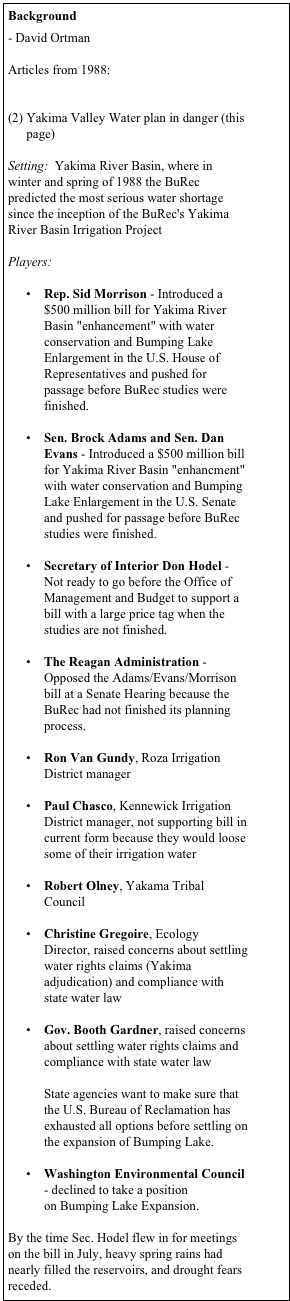

Yakima Valley water plan in danger

By James Wallace

Seattle PI July 20, 1988

YAKIMA – A few months ago, when Rep. Sid Morrison asked Interior Secretary Donald Hodel to come here, farmers were bracing for the most serious water shortage since this desert was transformed into rich farmland by a massive irrigation project early this century.

Mountain reservoirs that supply precious irrigation water to thousands of farms along the Yakima River were at record low levels. The water shortage threatened hundreds of millions of dollars in crops, as well as the land that is home and a livelihood to generations of farmers.

By last Friday, however, when Hodel finally came to town and flew with Morrison over those reservoirs high in the Cascades, they were nearly full.

A crippling drought had been washed away by heavy spring rains.

So, too, it appears, have been chances for congressional action this year on a controversial $500 million bill that would increase the Yakima Valley’s supply of water, modernize a delivery system built with turn-of-the century technology, and go a long way toward resolving Indian water rights claims.

And with a new administration soon to take over in Washington, D.C., it could take several years to regain valuable momentum that carried the best hope yet for solving water problems older than most of the farmers around here.

“The Fat Lady has not sung, but she sure has cleared her throat,” said Ron Van Gundy, manager of the Roza Irrigation District, in summing up prospects for the bill this year.

Not only is time running out for Congress to pass major water legislation before going home early because of the elections, but there also remain significant disagreements among the competing interests for water in the Yakima Valley.

The bill doesn’t have a chance until those interests can agree on its language.

On his one-day stop in Yakima, Hodel met with irrigators, environmental groups and leaders of the Yakima Indian Nation – key players in the drama. He met separately with each group, and the three 20-minute sessions were closed to the press.

Afterward, he and Morrison talked to reporters.

“We need more water in the Yakima River Basin,” said Morrison, a Republican from Zillah who was an orchardist before going to Congress.

“We don’t know yet know [sic] how to get it, how to pay for it or how to divide it when we have it. But we are getting closer every day, so we are not about to back away from it.”

But time is running out this year, just as quickly as the water being released from the mountain reservoirs by the Bureau of Reclamation to irrigate thirsty farmlands that bake in 100-degree summer heat.

Hodel, who also came to Yakima to keynote a Morrison campaign fund-raising dinner, would not say if the Reagan administration will support the bill if the remaining problems can be worked out in the short time left.

In fact, Hodel said very little.

“I don’t think this was the biggest thing on his mind,” said David Ortman of Seattle, Northwest representative of Friends of the Earth and one of the environmentalists invited to meet with Hodel.

The administration opposed the Yakima enhancement legislation during a Senate committee hearing last month, saying the Bureau of Reclamation had not finished its planning process. Those studies should be completed by next month, according to a bureau spokesman.

Hodel told reporters Friday, “We are not in a position to go before the Office of Management and Budget and start talking about supporting legislation with a large dollar price tag on it . . . when we haven’t finished our studies. We would be blown out of the water so fast it wouldn’t be worth the effort.”

Supporters of the legislation have been trying to push through the bill this year, in part, because Sen. Dan Evans is retiring. His influence is considered crucial to the bill’s success in Congress.

There is also pressure to pass the bill now because it would help resolve many of the Yakima tribe’s water claims, which are otherwise headed for the courtroom later this year. The Indians want additional water for instream flows to help with Yakima River fisheries, and to irrigate reservation farmlands.

The search for water to nourish the dry but fertile farmlands of the Yakima Valley began in 1864 with the digging of the first irrigation ditch. By the turn of the century, private irrigation districts had asked the Bureau of Reclamation to dam rivers for more water storage. Those dams created the five reservoirs that supply irrigation water to the half-million acre Yakima Project.

The Yakima Project runs about 175 miles, from north of Ellensburg to the Tri-Cities. It supplies irrigation water to more than 12,000 farms, which produce about a quarter of the nation’s supermarket apples and many other crops. The water comes from the spring runoff of the mountain snowpack and from water stored in the reservoirs: Keechelus, Kachess, Cle Elum, Rimrock, and Bumping Lakes.

But there is not enough water to meet all the demands, particularly in water-short years.

The enhancement bill would improve those water supplies through conservation measures and enlargement of the Bumping Lake reservoir, the single-most controversial part of the package.

To environmentalists, Bumping Lake is sacred ground. The area was a favorite of William O. Douglas, the late Supreme Court justice for whom the surrounding 165,000-acre wilderness area is named. Douglas had a summer cabin at Goose Prairie a few miles from the lake, and spent many summers hiking trails in the shadow of Mountain Rainier.

“A solution that includes Bumping Lake is no solution,” Ortman said Friday after the meeting with Hodel.

“But we are willing to work with all parties to resolve the problems,” he added.

Others who met with Hodel also said they will continue working on a consensus so the bill can move ahead.

“I think we are getting pretty close to it (a compromise),” said Robert Olney, member of the Yakima Tribal Council and secretary of the tribe’s irrigation committee. But Olney gave a hint of the possible legal battles ahead when he added: “We can’t continue to see our legal waters going to other uses.”

Judy Turpin of the Washington Environmental Council, another environmentalist who met with Hodel, also was optimistic a solution will be found.

“I think there is hope we can get somewhere with this,” she said. But Turpin predicted it would be “past this administration before we see a solution.”

Unlike Ortman’s group, Friends of the Earth, the council has not taken a position on Bumping Lake.

But there are other problems that must be worked out besides Bumping Lake.

Even if Bumping Lake is enlarged some 13 times as proposed, there would still not be enough water. For the Yakima Indians to get the additional water they are seeking, irrigation districts would have to use less. The enhancement bill would provide huge sums of money to improve water-delivery systems, but some districts are still uncomfortable with the concept of making less water go further, particularly those districts with senior water rights.

Storage water is allocated to irrigation districts under what is call the 1945 Consent Decree. It’s principle is the old water rights law of the West: First in time, first in right. Those irrigation districts that were built first have senior water rights. Others, such as the Roza, came later and have junior rights, meaning their water is rationed first in water-short years like this one.

This year, junior districts will get about 82 percent of their normal water allocation, not as much as they would like, but a significant improvement from several months ago when they faced the financially devastating prospect of getting less than half their water.

This is the third consecutive year of below-normal water supplies in the Yakima Valley. Last yaer was the driest ever in the valley. Junior districts were ordered to shut off water to their customers a month early. Roza farmers, for example, received only 68 percent of their water.

“We support this process, but we are not endorsing the bill in its present form,” said Paul Chasco, managers of the Kennewick Irrigation District, which would lose some of its irrigation water to increased stream flows for fisheries under the enhancement legislation.

“A lot more negotiations are needed,” Chasco said.